SECOND EDITION

Paperback | July 2018 | $ 39.99

ISBN: 9781486308163 | 168 pages | 245 x 170 mm

Publisher: CSIRO Publishing

Illustrations, Photographs

ePDF | July 2018

ISBN: 9781486308170

Publisher: CSIRO Publishing

Available from eRetailers

I found this book extremely interesting and easy to read. Gisela catches your attention immediately as she relates a story of three rescued Tawny Frogmouths at a veterinary clinic, sitting on a perch right next to the receptionist. They kept so still, even with a Great Dane sniffing at them and eyeballing them, that people thought they were toys! This ability to keep still is the essence of peoples’ fascination with them. Tawny Frogmouths also seem to be adapted to human presence and are common in parks and gardens and people’s backyards. In fact, recent surveys have found the presence of Tawny Frogmouths has increased with urbanisation, relative to Owlet Nightjars and Southern Boobook Owls.

The author uses phylogeny to demonstrate where Owls, Owlet Nightjars, Frogmouths, Nightjars and Oilbirds fit genetically compared with other birds. She talks about the Tawny Frogmouths’ distribution in Australia, which seems to include a wide range of climates—except arid desert and monsoonal regions.

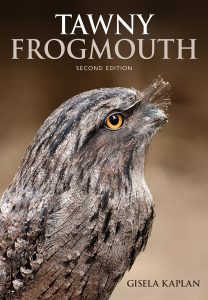

Gisela then discusses their anatomy and their nervous system. They apparently don’t have a preen gland but are able to be one of the best waterproofed birds (apart from water birds) that the author has ever come across. This seems to be due to their feathers, which are referred to as ‘powder-down’ feathers, which produce a waxy coating. Gisela then goes into a description of feathers and downy feathers generally speaking for birds, and filoplumes, semi-plumes and bristles which can be found in large numbers around the beak. Tufts on top of the beak are rare, and specific to the Tawny Frogmouths.

Birds’ hearing and vision generally speaking are very good, and they can detect moving prey items. Barn Owls can hunt in the dark, whereas the Tawny Frogmouth prefers to hunt with some light. Tawny Frogmouths have a large brain relative to body size. Their eyes are very large; they can see in dim conditions but can still fly in daylight. There are quite a few photos of different bird brains in the book, comparing optic, coordination and sensory areas. The pictures also show the frontal position and visual fields of the eyes of different owls, Tawny Frogmouths, birds of prey and a pigeon, which is quite interesting. Tawny Frogmouths can be prey to such things as large monitors, cats and foxes that climb the trees.

In roosting, the birds have good markings and camouflage and also adopt a camouflage posture with the head upwards and often have their body pressed against the tree trunk. They also have the ability to keep their eyes open slightly but still be asleep.

In low daylight, the Tawny Frogmouth can use crepuscular (twilight) hunting. They prey on terrestrial and aerial rodents, invertebrates, frogs and lizards. Tawny Frogmouths are susceptible to human introduced chemical poisons and even diseases from rats. Tawny Frogmouths seldom drink but seem to be able to get enough fluids from their prey.

Tawny Frogmouths have strong partnerships which can last for six years. Both parents spend a fair bit of time building nests for their young; sometimes they reuse leaves and grass stems from the previous year.

The chicks are very fluffy and well camouflaged, so can be left alone. If danger comes the chicks can raise their hackles and fluff up even more. If the nest is getting threatened the parents can spray urine and pungent faeces at the predator.

Gisela has a great love for the Tawny Frogmouths and is very knowledgeable about them right across Australia.

Maureen Gardner