NS Branch Meeting June 2023

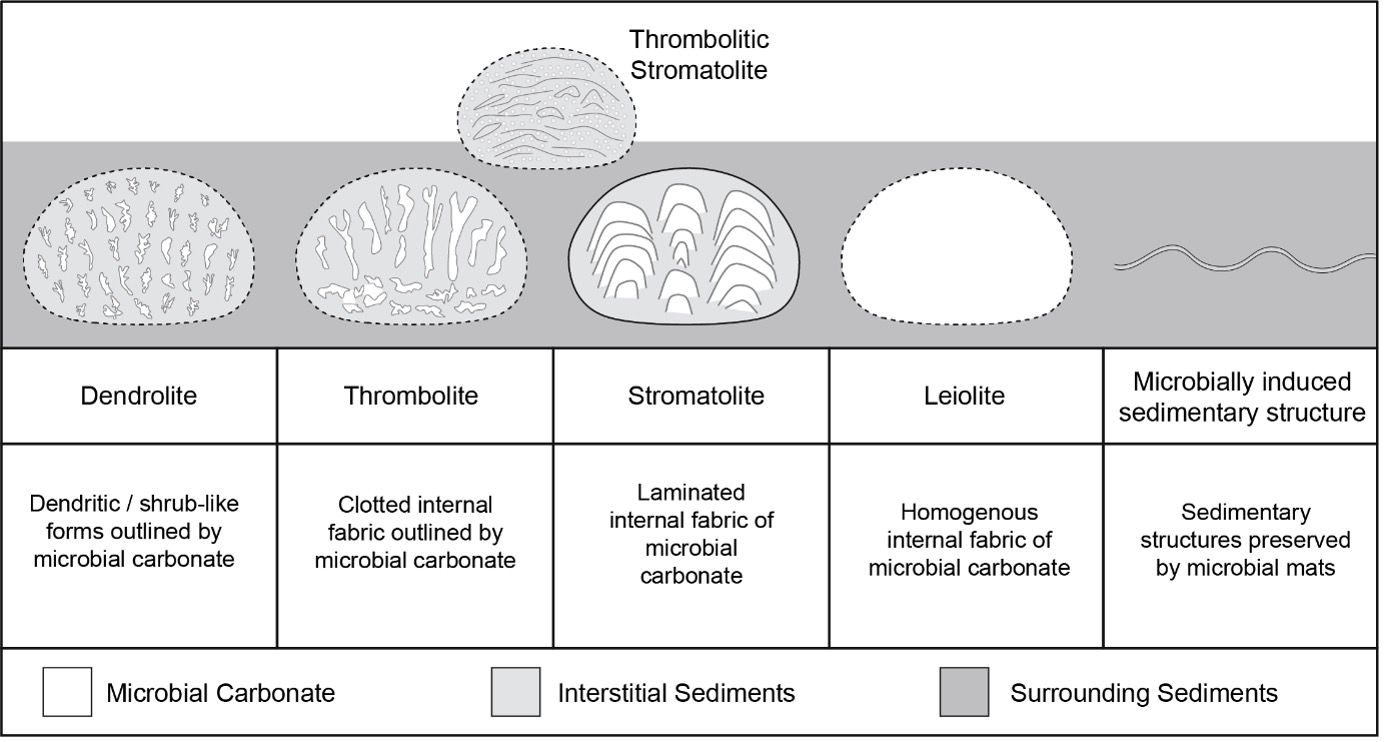

Unless you have studied stromatolites in the same detail as our speaker, you could be forgiven for thinking of “stromatolite” as the general term given to any organo-sedimentary structure formed via microbial activity, when in fact, as we learnt, a stromatolite is just one of a continuum of structures known as microbialites.

Our speaker for the month, Liam Olden, Senior Geologist at the Geological Survey of WA, culminated a childhood love of bones and fossils by undertaking a master’s degree at Curtin University researching microbialites.

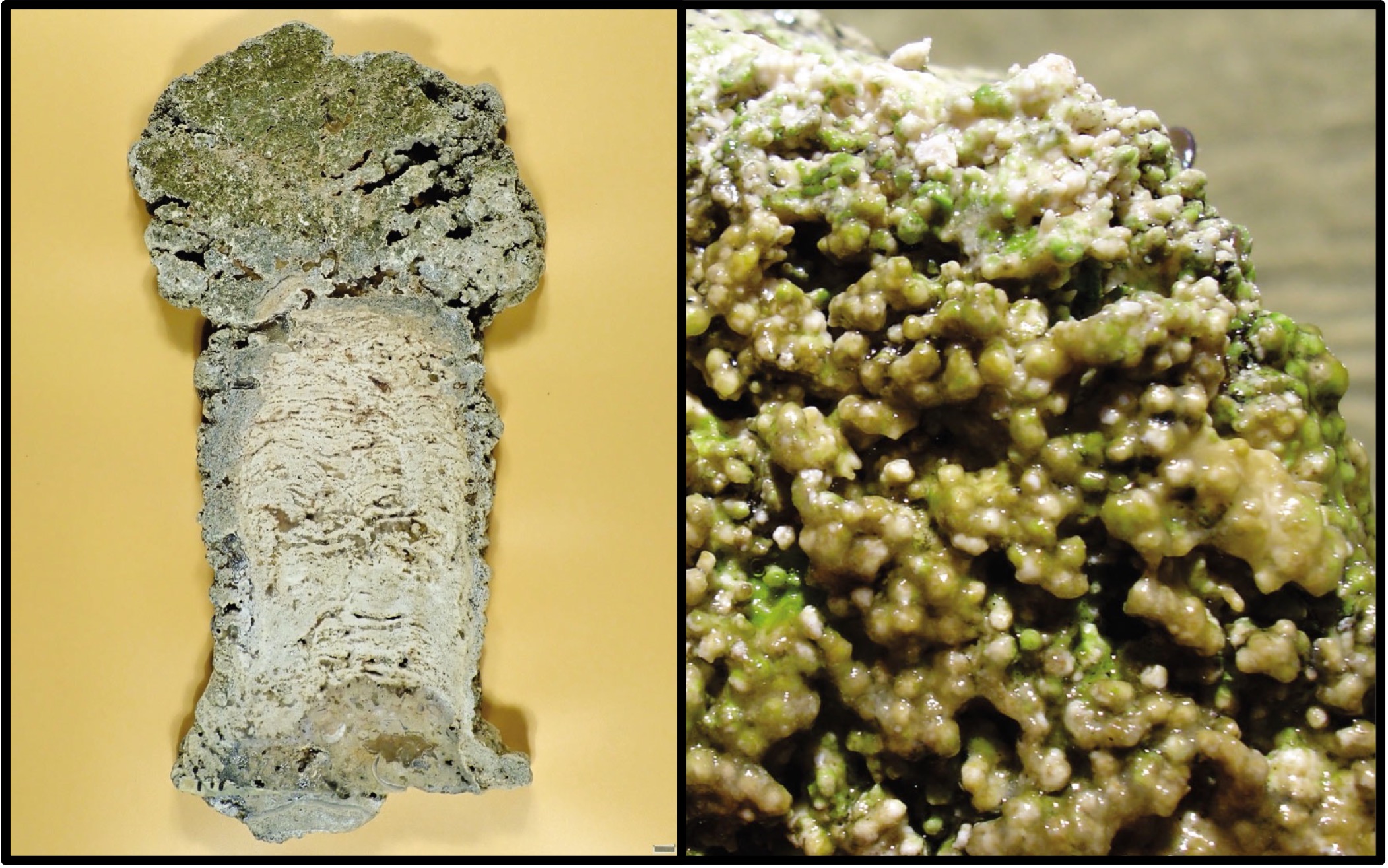

Liam began his presentation by explaining that microbialites are now classified on their morphology and internal structure – a stromatolite has a laminated interior fabric of microbial carbonate compared to a thrombolite with clotted interior fabric – resembling a cauliflower.

Hence, while we call the microbialites in Lake Preston and Lake Clifton thrombolites, this is not because they grow in freshwater but because of their morphology. It’s even possible for a stromatolite to transform into a thrombolite if the environment changes.

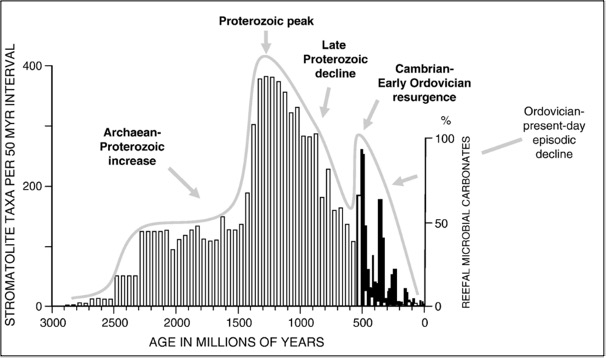

Grey & Awramik, 2020

Liam then concentrated the rest of the talk on stromatolites. A stromatolite’s only living part is the upper surface’s microbial layer. This is usually, but not always, a mat of cyanobacteria, or as Liam referred to it, ooze, on the lake or sea floor. As bacteria are photosynthesizing organisms, they initiate the precipitation of calcium carbonate by depleting the carbon dioxide in the water. As the inorganic layer consolidates, the organic layer of bacterial filaments grows upwards through the sediment to form a new layer, thereby repeating the process.

We learnt what controls stromatolite macrostructures is determined by the magnitude of the environmental influences versus the magnitude of the biological influences. Laterally alternating stromatolite forms are biologically driven, while fluctuating ecological conditions give rise to vertically alternating stromatolitic forms.

From a size aspect, studies indicate large structures are found in calm conditions, while high-energy environments give rise to smaller structures. However, regardless of the energy, stromatolites throughout geological history have been restricted to lacustrine, lagoonal and no deeper than mid-shelf waters.

Western Australia has the oldest microbialites in the world. Based on the dating of inclusions within zircons trapped in the inorganic layer, they are calculated to be 3.42 billion years old. Taxa maxima occurred about 1.2 billion years ago, with secondary peaks throughout the Phanerozoic period, which began about 540 million years ago.

A closer examination of these peaks indicates they occurred soon after mass extinction events. It is postulated that each catastrophic event substantially reduced the number of grazing organisms, thereby allowing microbes to thrive.

Liam isn’t the only person researching WA’s rich stromatolite history. In late June, scientists from NASA visited several sites in the Pilbara to collect stromatolites of different ages. Why? NASA is planning to collect Mars rock samples and return them in the mid-2030s. It is hoped these rocks will contain indications of primitive life that can be compared with the WA stromatolites.

Don Poynton