Main Club 3rd September 2021

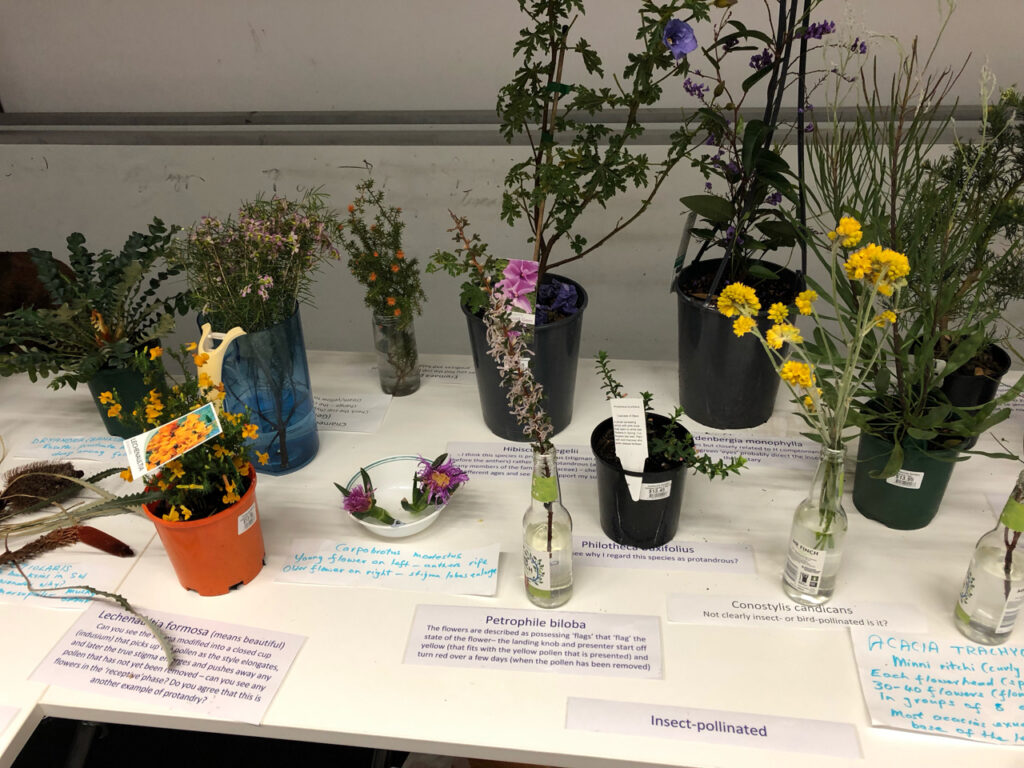

At our September meeting, our speaker was botanist Professor Byron Lamont. Byron entertained us with the pollination of the plants of South-Western Australia. There are three main groups of pollinators: insects, birds and mammals. Each plant species has unique traits designed to improve pollination efficiency: the transfer of pollen to the stigma, the first step in fertilisation.

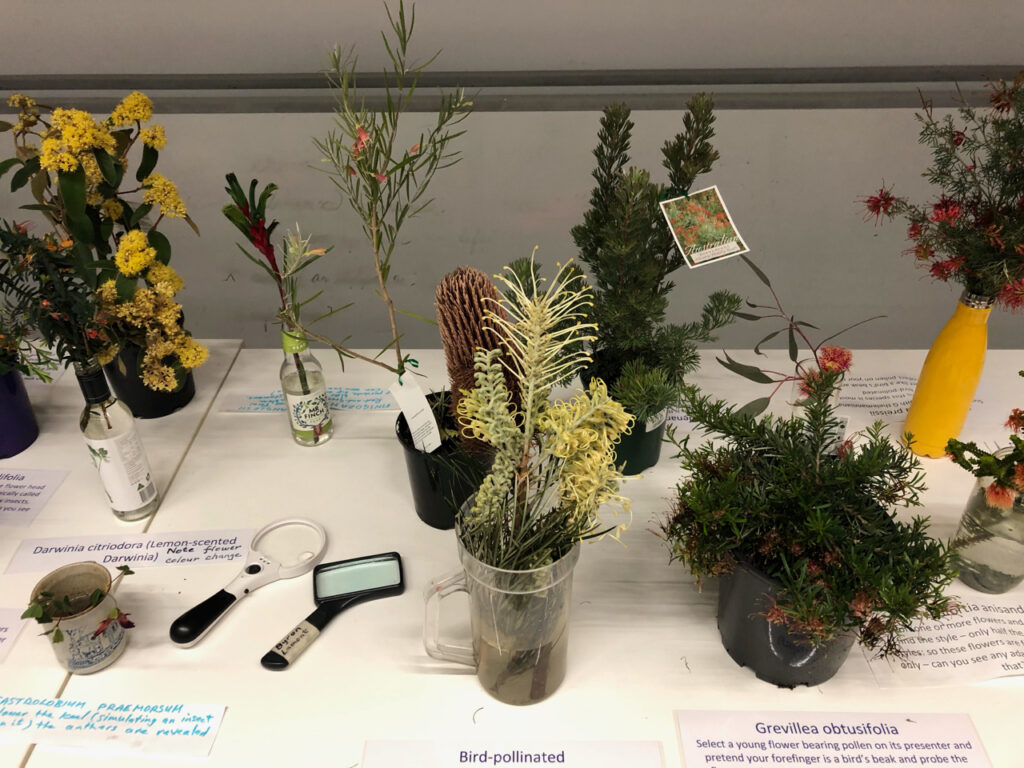

Byron used banksias to show examples of all three pollinator types. The Mud Wasp (insect pollinator) climbs into the Banksia lemanniana to get to the nectar, and they get covered in pollen. The Honey Possum (mammal pollinator) uses its feathery tongue to reach into the flower of the rare Banksia tricuspis to get the nectar. The flower has hooked styles that point downwards and rub pollen onto the Honey Possum’s back. As mammals tend to be night pollinators, flower colour is not essential. Byron showed a White-cheeked Honeyeater (bird pollinator) feeding on a Banksia menziesii. The Honeyeater uses the flower head as a landing platform and feeds from the opening front where most nectar and pollen are located and where pollination occurs. The colours of bird-pollinated flowers are usually bright red, orange, or green.

Insects have many ways to pollinate plants. Byron explained how the Calytrix flower is a stunning example of a butterfly-pollinated group. The butterfly’s long proboscis reaches deep into the flower to reach the nectar. We learnt about buzz pollination (sonication), where the bee vibrates the anthers of a Dianella with its wings, and the Blue-banded Bee can knock its head on anthers 350 times per second to dislodge the pollen from the anther. Byron showed us a photo of a male Ichneumon Wasp landing on the labellum of a WA Slipper Orchid, which mimics the female wasp. The male wasp backs onto the anther-bearing column and picks up the pollen held in two sacks.

Byron’s study of Hakea found insect-pollinated hakeas have small flowers, many very sharp spines, small leaves and little floral cyanide. In contrast, bird-pollinated hakeas have larger flowers, few spines, larger broad leaves, longer, stronger stems and higher floral cyanide. The red flowers (but not the nectar) are usually high in cyanide to deter emus, black cockatoos, and kangaroos from eating them. Byron talked about the rewards offered to the pollinators: great, frustrating, hidden or none at all! Most offer nectar and/or pollen, some a resting or mating place, while some orchids mimic the look and odour of female insects to attract the males. The Hammer Orchid’s articulated labellum throws the male Thynnid Wasp against the anther and stigma as he tries to fly away with the ‘female wasp’. Bryon spoke about the obnoxious (or sweet to some) odour of ‘smelly socks’ Grevillea and exploding pollen in Synaphea and Conospermum flowers.

Byron lastly discussed his latest passion studying fire-stimulated flowering. Examples included the Pyrochis nigricans (Red Beaks Orchid), Drosera zonaria, Verticordia grandis, the Grasstree Kingia australis, and the Macrozamia riedlei.

Insect pollinated

Bird pollinated

Tanya thanked Byron for his fascinating talk that was enjoyed by all and then gave us a brief update on how the critically endangered Western Swamp Tortoise is being assisted in colonising further south due to climate change. We were also shown an insect larva that a fungus has parasitised, and others proved that fungi were still popping out and about around Perth.

Ruth Clark