NS Branch Golly Walk 23rdJune 2021

Before starting our walk, Don Poynton, a retired geologist, explained to those who had not attended Dr. Sarah Martin’s presentation the week before the significance of Geoheritage sites and the history of their registration in Western Australia.

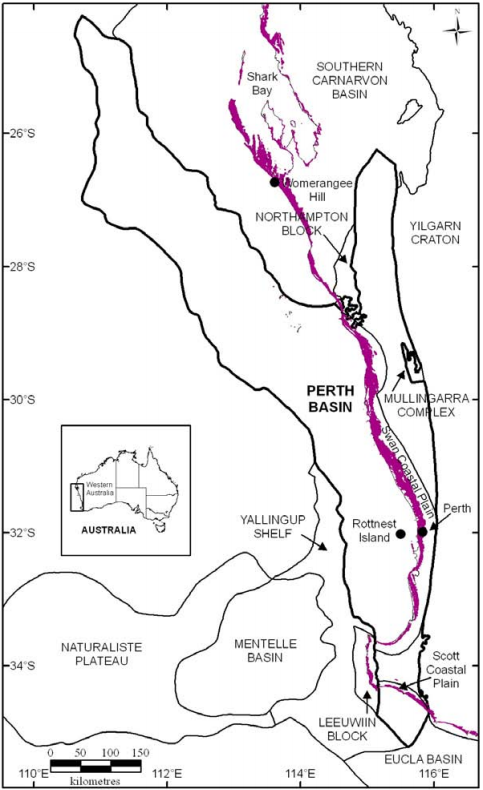

Don then explained that the Tamala Limestone at Peppermint Grove is part of one of the largest rock units in the world as it stretches for more than 1000km between Shark Bay and Esperance, is up to 10km wide onshore and up to 40km offshore.

Tamala Limestone in purple.

Jorgensen 2012 fig. 2.1

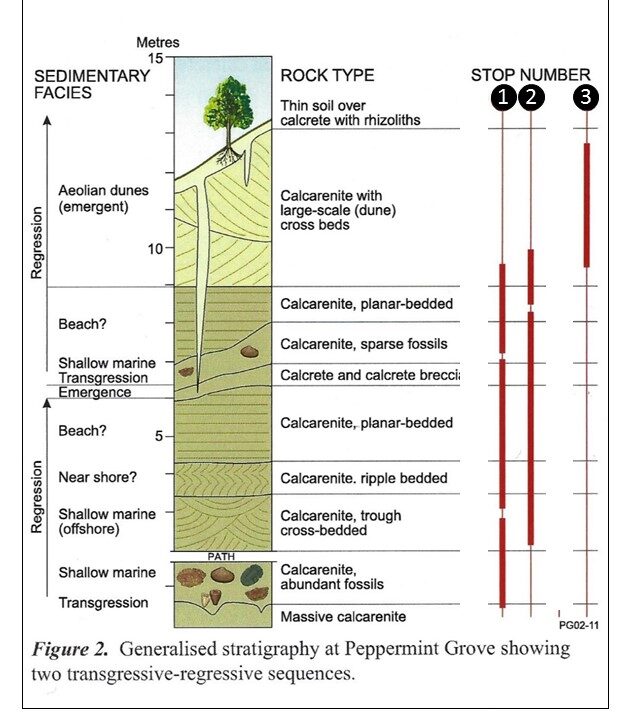

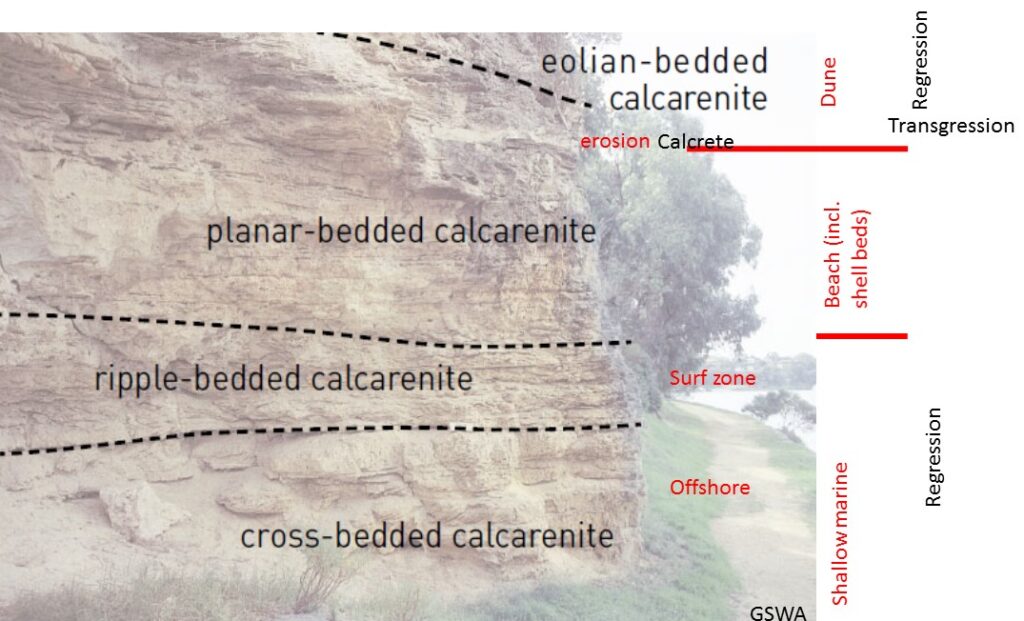

While often referred to as an aeolian (wind formed) dune system, Don explained the Peppermint Grove site demonstrated much more geological variability as there is evidence of shallow marine beds and beach deposits, which can be recognized by the fossil shells or by the nature of the bedding (see stratigraphic section).

About 50 years ago, the ratio of the two Oxygen isotopes O16 and O18 in shells could be used to distinguish between warm and cold water. Low O18 values indicate warm interglacial intervals, and high levels of O18 signify cold glacial periods. If sufficient measurements are taken from a vertical section of rock, the resultant values can be used to draw a continuous curve that mirrors the sea-level curve. The highs and lows are referred to as Marine Isotope Stages (MIS). The exposures at Peppermint Grove fall between MIS 7 and MIS 9, which correspond to approximately 300,000 to 240,000 years before present. This means that the Tamala Limestone we examined is considerably older than the Tamala Limestone sections we examined on Rottnest Island, all younger than 140,000 years. Armed with this information, we then examined three cliff sections.

The first outcrop showed a sequence that demonstrated regression of the coastline – the lowest exposed beds contained numerous shells indicating shallow marine deposition. Above this section, fossils are absent, and the calcarenite is planar bedded, indicating a beach. A layer of calcrete at the top marks an ancient soil layer which presented an opportunity for Don and Peter Alcock to point out and explain how rhizoliths are formed.

Modified from Bunting, A Field Guide to Perth and Surrounds.

Don had one of the participants measure the inclination of the beds (using a clinometer) to demonstrate that the low angle fitted the model of the beds having been deposited underwater and not sub-aerially.

Don explained at the second stop that it is vital to examine outcrops in three dimensions if possible. To demonstrate, we examined beds that looked like planar bedding from one direction, but when viewed around the corner, they were seen to be cross bedded.

Our last stop was near the top of the cliff, where the angle of the beds (geologically referred to as the dip) was measured to be around 32 degrees, and the direction of the slope (the dip direction) was 22 degrees from North. These measurements indicated these were ancient dunes formed by winds blowing from the south-southwest. From the top of the cliff, we were able to view the circular nature of Freshwater Bay, suggesting it may have once been one of the lakes, like Lake Claremont, situated in a swale that parallels the coast. GOLLY, I never thought of that.

Don Poynton