Northern Suburbs Branch 18th August 2021

Dr Anna Hopkins, Senior Lecturer in the Molecular Ecology and Evolution Group at ECU’s Joondalup Campus, provided our very well attended meeting with an insight into her current research into understanding the link between mycorrhizal fungi and ecosystems.

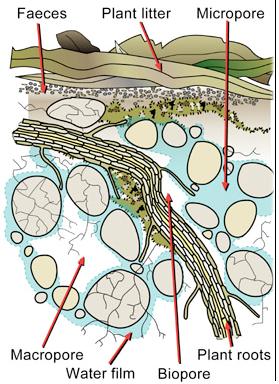

Anna began by describing the many habitats for biota that exist in the soil and the roles each one plays. This commences with the plant litter at the surface which carries its own clusters of bacteria and fungi. Within the soil, there are biopores formed by roots and burrowing invertebrates, macropores that are the air-filled pores providing habitats for non-aquatic, air-breathing organisms, and micropores, which remain filled with water after rain, thereby providing habitats for aquatic soil organisms.

Soil Biota Habitat – Image by Hopkins

Within these habitats, live approximately one quarter of the global biodiversity. Anywhere between one million and one billion bacteria can live in a teaspoon of soil, while on a global scale, soil is the next most important carbon sink after the oceans. Anna then introduced us to the three functional types of soil fungi; Saprotrophs which are the decomposers and are important for recycling nutrients, Pathogens which cause death but again are important for nutrient cycling, and Mutualists which live alongside their host and can be beneficial or have no effect.

The benefits of mycorrhizal fungi were clearly shown in photos of trials of Eucalyptus globulus seedlings planted in soils with and without mycorrhiza. The superior seedlings in the former demonstrated how nutrient and water uptake, assisted by the fungi, improved growth rate.

E. globulus after 12 weeks with and without mycorrhiza – Image by Hopkins

Anna then discussed some case studies that demonstrated how disturbance of the soil can impact soil fungi diversity – sometime positively but often negatively. Researchers from ECU and Murdoch University have been studying the effects of the 2011 drought in the Northern Jarrah Forest.

Using DNA based techniques, the group found that soil taken from beneath Jarrah trees at drought sites contained roughly the same number of fungi, but the functional groups and therefore fungi species had changed.

Northern Jarrah Forest showing patches affected by 2011 drought.

Photo: George Matusick, May 2011

It is predicted consequently; it will be more difficult for regrowth to occur. The group also studied the added effect of fire on drought on the forest. In this case the species richness was almost fifty percent less in the burnt areas.

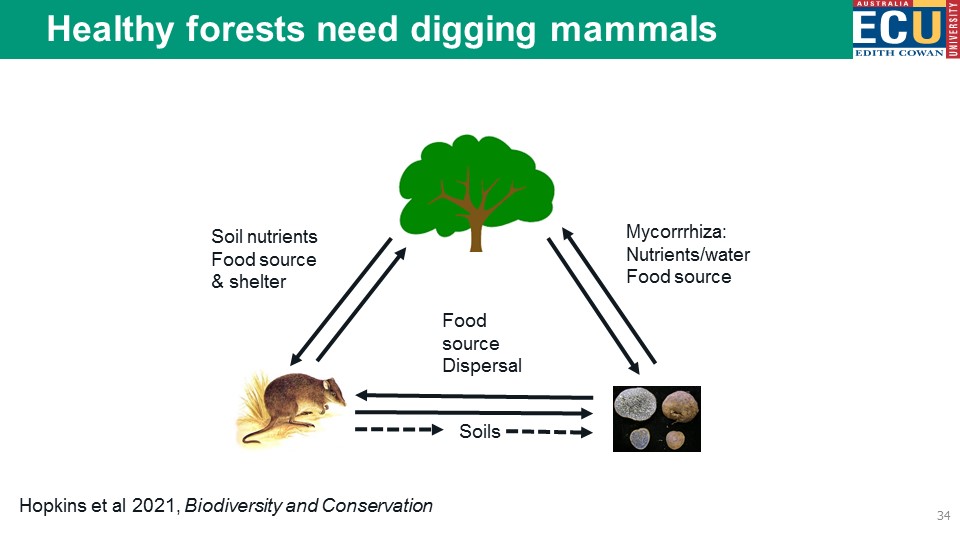

For the final section of her talk, Anna presented the results of studies by researchers from ECU, Murdoch, and UWA, on the benefits of digging mammals, such as Woylies and Quendas

The pits dug by these animals, not only turn over large amounts of soil, up to 5.9 tonne per year for Woylies and 3.9 t/y for Quendas, but the pits also accumulate litter which, when broken down by bacteria and fungi, recycles nutrients. The disturbance also allows greater water infiltration which in turn aids germination and plant growth. But most of all, digging provides a mechanism for fungal dispersal and recruitment.

Anna’s concluding remark was that the loss of mycorrhizal species is and will lead to changes in ecosystem functions and resilience.

Don Poynton